To Be or Not to Be: That Is the Question

Debunking the Claim That Mecca Did Not Exist Before Islam

In recent years, a small group of revisionist writers and missionaries have revived an old and repeatedly debunked claim: that Mecca did not exist, or was insignificant, before Islam. These assertions are often recycled without serious engagement with primary sources, the Arabic language, or the broader religious culture of pre-Islamic Arabia. Many of those advancing these arguments neither speak Arabic nor understand Qurʾānic or pre-Qurʾānic Arabian religion.

The claim usually follows a predictable pattern. First, Mecca is dismissed as an insignificant settlement. Then alternative locations are proposed—most commonly Petra, sometimes Yemen or other South Arabian sites. Finally, the Kaʿba itself is portrayed as a late Islamic invention imposed retroactively upon history.

This entire framework collapses once the discussion is reframed correctly. The historical question is not whether Mecca was a major imperial city. It is this: where was the sacred quadrangular sanctuary, housing a revered stone, that Arabs from across the peninsula venerated through pilgrimage?

Across Arabia, there were many settlements, markets, and temples. But only one sanctuary possessed all of the following:

• A quadrangular structure

• A sacred stone embedded within it

• Pan-Arab pilgrimage

• Neutral sanctuary status

• Recognition across tribal boundaries

That sanctuary was the Kaʿba in Mecca.

Ptolemy and “Macoraba”

The Greco-Roman geographer Claudius Ptolemy (2nd century CE) mentions a place called “Macoraba” in his Geographia. Many scholars have understood this as a Greek rendering of Makkah or a related sanctuary designation. While the identification has been debated, its presence in a scientific geographical work confirms that a significant settlement or sacred site existed in western Arabia long before Islam.

First-Century Evidence: Diodorus Siculus

In the 1st century BCE, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus describes a highly revered temple in Arabia, honoured by all Arabs. He does not name the site—but that omission strengthens the argument rather than weakens it. No other sanctuary in Arabia was universally revered. Regional temples in Yemen, Petra, and South Arabia served local cults only. Diodorus’ description fits only the Kaʿba.

Second-Century Evidence: Maximus of Tyre

Maximus of Tyre, a 2nd-century Greco-Roman philosopher, describes Arabs worshipping a quadrangular stone. He does not describe a city or kingdom, but a sacred stone object. There is no evidence anywhere in Arabia—whether Petra, Yemen, or elsewhere—of such a quadrangular stone sanctuary except the Kaʿba.

This testimony is preserved and discussed in the 1897 missionary work Arabia, the Cradle of Islam, whose author acknowledges the antiquity of the Kaʿba and the Muslim belief that the Black Stone descended with Adam and that Abraham rebuilt the sanctuary.

Pagan Arabia Was Not Empty – But It Was Fragmented

Arabia, especially Yemen (Arabia Felix), was religiously rich long before Islam. Greek and Roman writers such as Strabo and Pliny the Elder describe South Arabian temples, sacrifices, priesthoods, and cults tied to agriculture, rain, kingship, and the incense trade. Thousands of South Arabian inscriptions confirm these practices.

Yet every one of these cults was local. Yemeni temples were dedicated to specific gods such as Almaqah, ʿAthtar, and Wadd. They were bound to kingdoms, tribes, and cities. No Yemeni sanctuary functioned as a neutral, pan-Arab religious centre. There was no sacred stone uniting Arabian religious consciousness.

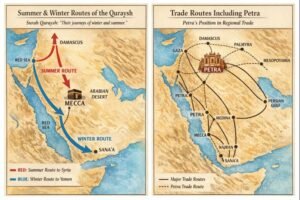

The Same Pattern Appears in Petra

Petra was an impressive Nabataean city with monumental architecture and temples. Its religion, however, was civic and ethnic, tied to Nabataean political identity. No ancient source describes Petra as a sanctuary of all Arabs. Its betyls were local cult objects, not universal sacred stones. Petra was a city with temples;

WHY THE PETRA–QIBLA ARGUMENT EXISTS — AND WHY IT FAILS

This section is intended to be inserted into the main article after the Petra discussion and before the conclusion or Abraha section.

At this stage, a critical question must be addressed directly: Why do proponents of the Petra theory rely so heavily on early mosque orientations (qibla) if Petra itself was neither a sanctuary nor a pan-Arab religious centre?

The answer is straightforward: because they lack direct historical evidence.

There exists no ancient source—Greek, Roman, Arab, Syriac, Jewish, or Christian—that identifies Petra as the Kaʿba, the destination of Arabian pilgrimage, the holder of a sacred stone comparable to the Black Stone, or the religious axis of Arabia. Unable to demonstrate Petra’s sanctity through texts, ritual memory, or archaeology, revisionists turn instead to an indirect and technical claim based on mosque orientation.

WHAT THE PETRA–QIBLA ARGUMENT CLAIMS

The argument asserts that some early mosques do not align precisely with modern Meccan coordinates. When their walls are projected backward on modern maps, these alignments are said to intersect near Petra. From this, it is inferred that Petra must have been the original qibla.

This claim rests on several false assumptions.

FALSE ASSUMPTION ONE: MODERN CARTOGRAPHIC PRECISION

Early Muslims did not possess latitude–longitude grids, satellite measurements, global cartography, or standardised surveying instruments. Qibla determination relied on approximate cardinal directions, astronomical observation, regional convention, and inherited practice.

Classical jurists consistently held that facing the general direction (jihah) of the Kaʿba was sufficient, especially at long distances. Variation in early mosque orientation is therefore expected and well attested.

FALSE ASSUMPTION TWO: A SINGLE MATHEMATICAL POINT

Early mosques were oriented toward a sacred direction, not a Cartesian coordinate. Mosques in Iraq broadly face south; in Yemen, north; in Syria, south or south-east. This diversity reflects approximation toward Mecca, not uncertainty about the qibla.

FALSE ASSUMPTION THREE: PETRA WAS SACRED ENOUGH TO BE A QIBLA

This is the decisive failure. Even if an alignment appears to intersect near Petra, the fundamental question remains: why would Petra serve as a qibla at all? A qibla presupposes sanctity; it does not create it.

Petra was a politically controlled Nabataean and later Roman city. It imposed tolls, required permission for access, housed local civic cults, and lacked any universally revered sacred object. It possessed no Black Stone, no neutral sanctuary status, no pan-Arab pilgrimage, and no continuous ritual memory.

WHY THE ARGUMENT PERSISTS

The Petra–qibla argument persists because it bypasses Arabic and Islamic sources, appears technical to non-specialists, and shifts the burden of proof away from the absence of historical evidence.

THE QUESTION THAT ENDS THE DEBATE

Where is the evidence that Petra was sacred to the Arabs? There is none.

No shrine. No stone. No sanctuary. No pilgrimage. No continuity.

The Petra-qibla argument exists not because Petra was important, but because revisionists lack any direct evidence linking Petra to Arabian pilgrimage, sanctity, or ritual. Early mosques were oriented using approximate methods, facing the general direction of Mecca, not a cartographically precise point. Even if some early structures appear to align toward Petra, alignment alone cannot establish sanctity. A qibla presupposes an already sacred centre—and Petra was never such a centre in Arabian religious history.”

By contrast, Mecca’s sanctity is independently attested through Greco-Roman testimony, references to a quadrangular sacred stone, continuous pilgrimage, the accumulation of 360 idols, protected trade, and attacks directed at Mecca rather than elsewhere.

Geometry cannot replace history. Lines on maps cannot overturn ritual, memory, continuity, and testimony. The qibla points to an already sacred centre; it does not invent one.

Mecca was a sanctuary for Arabia.

Why Mecca Was Different

The Kaʿba’s Four Corners (Arkān) — and Why Petra-Qibla Logic Fails

The Kaʿba is not a circular structure with a single “forward-facing” side. It is a quadrangular sanctuary with four corners (arkān), each traditionally named and oriented toward different regions of the world.

These are not modern inventions; they are pre-Islamic and early Islamic realities.

The Four Corners (Arkān)

-

Rukn al-Aswad – the Black Stone corner

-

Rukn al-ʿIrāqī – facing Iraq

-

Rukn al-Shāmī – facing Greater Syria

-

Rukn al-Yamānī – facing Yemen

This alone introduces a fatal problem for the Petra–qibla argument.

Mecca was not tied to one god, one tribe, or one kingdom. The Kaʿba housed 360 idols representing tribes across Arabia, including depictions associated with Jesus and Mary. It functioned as a neutral sanctuary where bloodshed was forbidden.

This explains why ʿAmr ibn Luhayy al-Khuzaʿī brought idols to Mecca from Syria—because Mecca was already the religious hub. A minor site does not attract hundreds of deities.

The Himyarite Jewish King

Centuries before Abraha, Islamic historical sources record a Himyarite Jewish king who intended to invade Mecca and Madinah. His rabbis warned him that a prophet would be born in Mecca and reside in Madinah. He abandoned his campaign and honoured the Kaʿba by contributing a covering for it. This tradition confirms Mecca’s sanctity long before Islam.

Paleo-Arabic Inscriptions and Allah

Modern epigraphic research by Ahmad al-Jallad has uncovered Paleo-Arabic inscriptions predating Qurayshi Arabic. These inscriptions invoke Allah by name, particularly in funerary prayers, showing that Allah was regarded as a supreme deity long before Islam. These inscriptions were found near Mecca, including Taʾif, reinforcing the Hijaz’s religious continuity.

Why There Is No Archaeology in Mecca

Mecca is a continuously inhabited sacred city. Like the Vatican or Temple Mount, it cannot be subjected to large-scale excavation. The absence of archaeology is not evidence of absence.

Abraha – The Icing on the Cake

Only after all this do we arrive at Abraha. Abraha built a cathedral in Sanaʿa to rival the Kaʿba. When Arabs ignored it, he marched north to destroy Mecca. If Mecca were insignificant, he would not have cared. His campaign proves Mecca’s unrivalled status.

Conclusion

The claim that Mecca did not exist before Islam is ideology, not scholarship. It ignores first- and second-century testimony, Greco-Roman geography, epigraphy, archaeology, and historical continuity. Arabia had many temples. It had only one sanctuary that transcended tribe and region. That sanctuary was the Kaʿba in Mecca.

References:

- Claudius Ptolemy, Geographia, Book VI, in J. Lennart Berggren and Alexander Jones, trans., Ptolemy’s Geography: An Annotated Translation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).2. Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, Book III, in C. H. Oldfather, trans., Diodorus of Sicily, vol. 2 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935).3. Maximus of Tyre, Dissertations, Oration 38, in Thomas Taylor, trans., The Works of Plato and Other Philosophers (London, 1804).

4. Samuel M. Zwemer, Arabia, the Cradle of Islam (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1897).

5. Strabo, Geographica, Book XVI, in H. L. Jones, trans., The Geography of Strabo, vol. 7 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932).

6. Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book VI, in H. Rackham, trans., Pliny: Natural History, vol. 2 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1942).

7. Christian J. Robin, “South Arabia, Religions in Pre-Islamic Times,” in The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity, ed. Scott Fitzgerald Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

8. Ahmad Al-Jallad, “Ancient North Arabian and Paleo-Arabic Inscriptions,” in The Semitic Languages, ed. John Huehnergard and Na’ama Pat-El (London: Routledge, 2019).

9. Ibn Kathīr, Al-Bidāyah wa’l-Nihāyah, vol. 2 (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah).

10. Ibn al-Athīr, Al-Kāmil fī al-Tārīkh, vol. 1 (Beirut: Dār Ṣādir).

11. Glen W. Bowersock, Roman Arabia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983).

12. Jodi Magness, The Archaeology of the Holy Land (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

—

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Al-Jallad, Ahmad. “Ancient North Arabian and Paleo-Arabic Inscriptions.” In The Semitic Languages. London: Routledge, 2019.

Berggren, J. Lennart, and Alexander Jones. Ptolemy’s Geography: An Annotated Translation. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Bowersock, Glen W. Roman Arabia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983.

Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca Historica. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935.

Ibn al-Athīr. Al-Kāmil fī al-Tārīkh. Beirut: Dār Ṣādir.

Ibn Kathīr. Al-Bidāyah wa’l-Nihāyah. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah.

Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1942.

Robin, Christian J. “South Arabia, Religions in Pre-Islamic Times.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Strabo. Geographica. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932.

Zwemer, Samuel M. Arabia, the Cradle of Islam. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1897.